Book, Histoire naturelle des oiseaux de paradis et des rolliers: suivie de celle des toucans et des barbus (Natural History of Birds of Paradise and Rollers: Followed by that of Toucans and Barbets), Volume 2; 1806; Written by François Levaillant (French, 1753–1824); Illustrated by Jacques Barraband (French, 1767–1809); Smithsonian Libraries, QL674.L65 1806

An exhibit at the Cooper Hewitt comes to my attention thanks to Dylan Kerr, whose essay The Mandarin Duck and Avian Art at the Cooper Hewitt makes an interesting link between the choices Rebeca Mendez made as a curator and a recent unusual bird sighting in New York City:

For the past several weeks, New Yorkers have been abuzz over a mysterious visitor. A mandarin duck, an intricately colored waterfowl native to East Asia, has taken up residence alongside the mallards in the Central Park Pond, drawing crowds and inspiring memes, dog costumes, and a Twitter account (bio: “I’m not from around here”). Pundits have argued that the frenzy betrays a desire for good news. But perhaps, the Mexico City-born designer Rebeca Méndez suggested the other day, something deeper is at play. “In our own normal life, we have patterns that we are so used to.

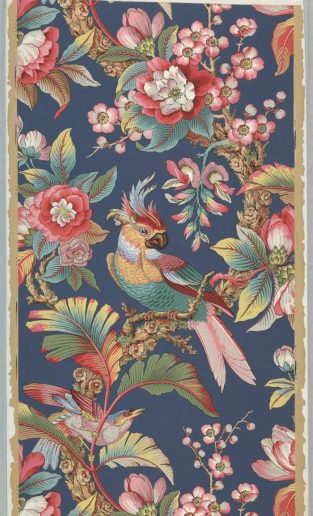

Sidewall; 1905–13; Manufactured by Zuber & Cie (Rixheim, Alsace, France); Block-printed on paper; Gift of James J. Rorimer, 1950-111-10

My immediate reaction is yes. We are bombarded with more negative information more quickly, more constantly than ever in my lifetime. We need relief, and nothing like an exotic bird coming to town to bring it:

When something”—an anatine interloper, say—“comes in and breaks that, it’s incredibly exciting,” she said. “The world suddenly collapses—it’s like a wormhole from far-east Asia to Manhattan.”

Méndez recently curated an exhibition of avian art at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, across the street from the Park. It’s part of the “Selects” series, in which the museum invites a guest to put together a show from objects in its collection. (Previous guest curators include the architect David Adjaye and Ellen DeGeneres.) Méndez, a National Design Award winner and the director of a U.C.L.A. design lab, focussed on birds partly in response to migration in the news. “We are setting our boundaries tighter and tighter—we are entrenching in our location,” she said. Birds, with their ability to fly away, “represent incredible freedom.”

On a recent Friday, Méndez and Christina De León, a Cooper Hewitt curator who worked on the show, took a spin through the galleries. In addition to items from the Cooper Hewitt’s holdings (a seventeenth-century falcon hood, a paper-clip-size flying robot), Méndez had included some two dozen taxidermied birds from the National Museum of Natural History, in Washington, D.C., home to six hundred and forty thousand-odd avian specimens collected by explorers and naturalists since 1818.

Inside a room filled with recordings of birdsong, Méndez and De León examined a display case holding a trio of preserved elegant trogons, small red-bellied birds from Mexico and Central America; each was lying on its back, its feet strung together. (Killing specimens for taxonomic research is still an accepted practice.) De León recalled the Museum of Natural History’s hesitation in lending the birds. “They were reticent because they didn’t want the specimens to be treated as curiosities,” she said. When the curators were granted access, the experience was shocking. “It’s just row after row of drawers,” De León said, as the crystalline song of a resplendent quetzal rang out from a speaker. Méndez, who speaks with a soft Mexican accent, nodded gravely. “You cannot help but, first of all, smell the formaldehyde,” she said. “And then you open, and you open to death.”…

Read the whole review here.